“Most of the problems that exist in youth sports result from the inappropriate application of the win-oriented model of professional or elite sport to the child’s sports setting (R.E. Smith 1984).”

“The difficulty lies not in the new ideas, but in escaping from the old ones.”

- John Maynard Keynes

In the logical process of motor acquisition and sequential learning, you must learn to walk before attempting to run. Movement literacy serves as the foundation for technical and tactical application in higher-level sport. In order to perform at high levels a basic framework of motor competency must exist. These building blocks provide the athlete with the appropriate tools to develop and economize physical preparation. Hockey is not an early specialization sport. In order to develop the qualities needed to excel on the ice, players need to be exposed to multiple stimuli at an early age both on and off the ice. The answer to enhanced skill development, including strength training, does not reside in playing more hockey games, specialized physical training, or placing adult values on childhood activities. The LTAD model seeks to aid and develop the athlete over the course of their athletic careers in order to maximize potential while sustaining passion and life-long love for sport. (1) Fundamental movement literacy is the bedrock for long-term athletic success regardless of sporting discipline. Furthermore, placing adult values and the need to win at all costs should never trump development and the early emergence of life long love for sport. This may compromise the learning process and lead to undesirable outcomes such as burnout, chronic injury and premature developmental issues.

Movement Literacy= Foundational human movement such as kicking, jumping, throwing, receiving, catching, bounding, tumbling and skipping that serve as a foundational prerequisites for advanced activity.

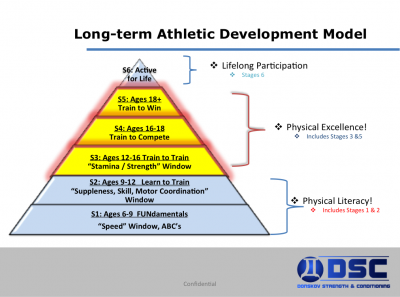

The long-term athletic development model seeks to take advantage of “biological training windows” and introduce skills during the optimum point of physical development. The model, pioneered by sports scientist Istvan Balyi creates a solid framework for young aspiring hockey players.

Long Term Athletic Development Model used to maximize athletic potential and create life-long physical activity.

FUNdamentals:

Ages 6-9

This is an important period where emotional ties to sport are developed. FUN is the name of the game. This is accomplished through small area games, multiple repetitions and authentically learning skills through a trial and error process, without being over-coached, or tied to rigid structure. Children areencouraged to enjoy in adult-free play, and learn through self-imposed cause and effect, trial and error experience. Agility, balance, coordination and the first biological window for accelerated speed adaptation occur during this period.

Learn to Train (70/30% practice to game ratio):

Ages 9-12

This is a period where motor coordination can be introduced and existing qualities maintained. Qualities such as throwing, receiving, balance; basic unloaded patterning such as squatting, hinging, pushing and pulling can all be learned during this stage of physical maturation. A larger movement “data base” allows the young athlete to reflexively respond to changing stimuli without hesitation and pre-learned habits that may hinder response time. ”If fundamental motor skill development is not developed between the ages of 8-11 and 9-12 for females and males, a significant window of opportunity has been lost.” (1) Coaches may introduce a dynamic warm-up focusing on movement efficiency, stability and dynamic mobility. The focus still resides in playing multiple games, multiple sports while simultaneously increasing movement variability. Movement literacy is developed during the first two blocks of the athletic based pyramid. It serves as the foundation of sport specificity and long-term participation. Failure to take advantage of these biological learning opportunities compromises future development and may hinder long-term skill acquisition.

Train-to-Train (60/40% practice to game ratio):

Ages 12-16

Structured strength and conditioning may take place during this physiological developmental window. Aerobic exercise may also be introduced, as the cardio respiratory system is now ready for the demands placed upon it. “Optimal aerobic trainability begins with the onset of peak height velocity. According to Hollmann, the greatest increase in heart volume occurs at approximately 11 years of age for girls, and approximately 14 years of age for boys (2). Special emphasis is also required for flexibility training due to the sudden growth of bones, tendons, ligaments and muscles. The skeletal system grows at an accelerated rate during this time and may place the soft tissue in a tight, facilitated state. During this period players can select a late specialization sport. This should typically occur between the ages of 12 and 15. From the experience of the author, the later this decision can be made, the better it will serve to advance overall athletic qualities pertaining to sport.

Train to Compete: (40/60% practice to game ratio)

Ages 16-18

The focus now shifts from general to specific in terms of development. Periodization and position specific training are introduced; as such structured ebbs and flows in the training process begin to take shape. Periodization simply means training in periods and provides the Coach with structure dividing the annual plan into a transition, preparation and competition blocks, each block representing various dates within the annual plan. Without a foundation of physical literacy, this period will not be economized appropriately and poor skill development may expose the athlete to inefficient and compromised performance.

Train to Win: (25/75% practice to game ratio)

Ages 18+

This period seeks to maximize all performance abilities. Physical preparation, psychological preparation, technical and tactical abilities are all coached on a solid platform of retained bio-motor abilities. Practice to game ratio is noticeably reduced, giving the athlete more time to focus on his/her specific skill set.

Active for Life:

There is a better opportunity to be Active for Life if physical literacy is achieved before the Training to Train stage. In other words, play multiple sports at an early age, don’t limit skill acquisition with early specialization, and thus develop a life long love for physical activity.

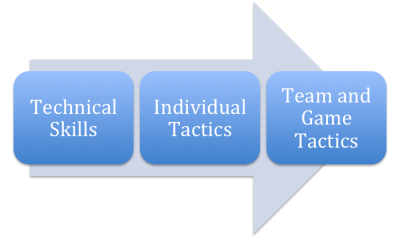

Slide courtesy of www.donskovhockey.com: Technical skills such as skating, shooting, puck handling and passing are paramount in the development process of the hockey player. In order to use individual and team tactics, fundamental technical skills must exist, the more skill, the more variability of specific tactics.

Factors Influencing the Model

10 Factors influence the LTAD model:

1.) The 10-year rule

2.) Fundamentals

3.) Specialization

4.) Developmental Age

5.) Trainability

6.) Physical, Mental, Cognitive, and Emotional Development

7.) Periodization

8.) Calendar Planning

9.) System Alignment and Integration

10.) Continuous Improvement

10,000 Hours

There are ten factors that influence the model and it’s ability to impact motor competency. For sake of brevity, the author will discuss two such factors. One of the major factors influencing the LTAD model is the 10,000-hour rule (Starkes and Ericsson). Research has shown that it takes 10,000 hours of deliberate practice to reach the pinnacle of any profession. For a player, or a coach, this translates into three hours each day for ten years. This is the time needed to harness physiological, psychological and neurological development. The base of this development is anchored by physical literacy. The structure of a pyramid is only as strong as it’s foundation. Without a strong, structural base, implosion will result. This can be in the form of poor skill levels, burnout, chronic injury and an eventual loss of passion for the game. You can’t shoot a cannon out of a canoe. The process of building strong, powerful hockey players cannot be attained without fist building appropriate requisite skills, and playing more games does not accomplish this goal. Skill acquisition is accumulated through constant repetition, deliberate practice and the use of free time. “In a study done by current NHL Coach George Kingston in1976 he found that the average player in the Canadian system spent 17.6 minutes on the ice during a typical game and was in possession of the puck for an astonishingly low 41 seconds. Kingston concluded that in order to get one hour of quality work in the practicing of the basic skills of puck control, (that is, stickhandling, passing, pass receiving and shooting) approximately 180 games would have to be played.” (3)

More games = < skill development, < skill development = < fun, < fun = < participation, < participation = > sedentary youth.

In the construction of 10,000 hours, deliberate practice, small area games, free time, and early exposure to varying sporting demands are much more important than the games themselves. Games should be adapted to fit the skill level of the athlete where basic skills, multiple puck touches, quick decision making, and skating mechanics can be challenged in a tight, confined, fun environment. It is during these formative years where the pillars of athletic achievement are harnessed. In addition, the 10,000 hours seeks to exploit motor efficiency by creating unconscious competence, whereby the athlete does not have to think to perform with precision and accuracy in response to changing conditions on the ice.

In the construction of 10,000 hours, deliberate practice, small area games, free time, and early exposure to varying sporting demands are much more important than the games themselves. Games should be adapted to fit the skill level of the athlete where basic skills, multiple puck touches, quick decision making, and skating mechanics can be challenged in a tight, confined, fun environment. It is during these formative years where the pillars of athletic achievement are harnessed. In addition, the 10,000 hours seeks to exploit motor efficiency by creating unconscious competence, whereby the athlete does not have to think to perform with precision and accuracy in response to changing conditions on the ice.

The 4 Stages of Learning a new Skill

|

Unconscious Incompetence |

Mistakes are made unconsciously. |

|

Conscious Incompetence |

By repetitive repetition and coaching the athlete recognizes these inefficiencies. |

|

Conscious Competence |

Proper skill is executed with thought and effort. |

|

Unconscious Competence |

Proper skill is executed effortlessly without thought. |

The goal of motor acquisition is to respond to a change in stimulus with a plethora of movement-based options. The more options the nervous system possess, the more choices it has in reaching the appropriate response efficiently.

At an early age (0-12yrs.), exposure is king. Kicking, running, jumping, throwing, tumbling, catching, receiving, decelerating, changing direction, skipping, hopping, balance and motor coordination are a few of the abilities that can be introduced early through small area games, plying multiple sports and the adequate use of uninterrupted, adult free, free time. This period also sets the stage of developing the requisites required to initiate strength and conditioning protocol during the “Learn to Train” period. If the athlete is unprepared physically when he/she reaches this biological period progress will be stalled and development compromised.

“Adapt the sport to the athlete, not the athlete to the sport.”

It is during the early stages of athletic development where free time and multiple exposures to various sports establish a large “data base” of movement literacy. The larger the database, the more options may be utilized during the demands of sport where decisions are not “memorized”, and creative response leads to superior performance outcomes. Ken Dryden sums it up quite eloquently:

“It is in free time that the special player develops, not in the competitive expedience of games, in hour-long practices once a week, in mechanical devotion to packaged, processed, coaching-manual, hockey-school skills. For while skills are necessary, setting out as they do the limits of anything, more is needed to transform those skills into something special. Mostly it is time unencumbered, unhurried, time of a different quality, more time, time to find wrong answers to find a few that are right; time to find your own right answers; time for skills to be practiced to set higher limits, to settle and assimilate and become fully and completely yours, to organize and combine with other skills comfortably and easily in some uniquely personal way, then to be set loose, trusted, to find new instinctive directions to take, to create.

But without such time a player is like a student cramming for exams. His skills are like answers memorized by his body, specific, limited to what is expected, random and separate, with no overviews to organize and bring them together. And for those times when more is demanded, when new unexpected circumstances come up, when answers are asked for things you’ve never learned, when you must intuit and piece together what you already know to find new answers, memorizing isn’t enough. It’s the difference between knowledge and understanding, between a super-achiever and a wise old man. And it’s the difference between a modern suburban player and a player like Lafleur.”

Painting that hangs in Kunsthishorisches Museum in Vienna done in 1561 by Pieter Brueghel depicting 230 children playing over 90 games in a town square.

Update of the painting to depicting Children of today.

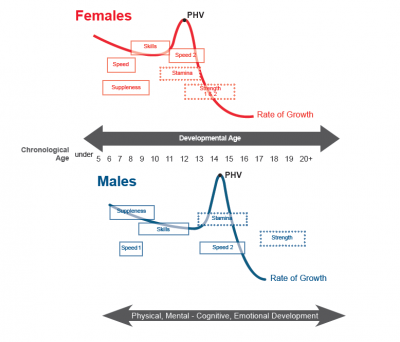

Trainability Windows

Another major factor influencing this model is the idea of biological training windows, or sensitive periods in athletic development. “The sensitive periods are periods in human life when the organs and systems that determine a given ability are under development.” (4)

“Developmental age refers to the degree of physical, mental, cognitive, and emotional maturity. Physical developmental age can be determined by skeletal maturity or bone age after which mental, cognitive, and emotional maturity is incorporated.” (1)

As we can see in the LTAD pyramid, FUNdamental basic skills such as agility, balance and coordination can be trained at an early age (6-9yrs.) through the use of fun and games. This can take place after practice, or during the summer months. Basic motor coordination can be attacked during the “Learn to Train” block. This is a window of opportunity to introduce a dynamic warm-up or games focusing on quickness and change of direction. It is only after the development balance, agility, and basic motor coordination where the strength and conditioning practitioner may safely address basic strength, suppleness and stamina without compromise.

Sensitive Periods of Training and Performance (Balyi and Way, 2005)

“Currently, most athletic training and competition programs are based on chronological age. However, athletes of the same age between ages 10 and 16 can be 4 to 5 years apart developmentally. Thus, chronological age is a poor guide to segregate adolescents for competitions.” (1)

The bottom line is that hockey player’s need a variety of exposure in ever changing learning environments without early specialization, pre-programmed, sport-specific drills focusing on outcome rather than process. Winning should not be stressed. The early years of an athlete’s career are when passion, love and emotional ties are set for life-long love of sport. The weight room is a highly structured, pre-programmed environment of controlled stress application. Prior to commencement, a solid level of physical literacy is paramount.

Final thoughts on Long Term Athletic Development:

1.) Athletes learn from trail and error. It is important that during development that the athlete be exposed to a variety of experiences. Hockey is NOT an early specialization sport.

2.) Early specialization limits motor variability and restricts motor learning. Too much specialized focus may lead to pre-programed responses to changing conditions on the ice. In addition, lack of free time and pre-packaged drills, in controlled environments inhibit creativity and natural development.

3.) The greater the database, the more efficient the nervous system.

4.) Always seek to expand the database.

5.) Umbrella Theory: A person with a large surface area umbrella of protection made of mobility, stability and strength is able to move freely under the umbrella without getting wet. (5) Focusing on the basics can prevent long-term chronic injury and set out to make the sporting experience fun and rewarding.

6.) Long-term athletic development increases motor efficiency. Efficiency = output relative to the cost of input.

7.) Limitations in movement = limitations in sport.

8.) Young athletes are NOT miniature adults.

9.) Strength and conditioning should be based on biological readiness. If you do not understand basic mathematics (physical literacy), you cannot perform advanced algebra (weight training)

10.) Players can select a late specialization sport when they are between the ages of 12 and 15. The later the better.

11.) Structured strength and conditioning for ice hockey should take place between the ages of 12-14.

12.) Don’t dream on behalf of you’re child.

13.) The more complicated the skill, the more heavily the athlete relies upon previously learned skills and abilities.

14.) Redefine performance metrics. Don’t keep score during early childhood development. 1.) Redefine Wining: focus on improvement and skill development, 2.) Fill “emotional” tanks by being positive and providing mentorship, 3.) Honor the game, the rules, the officials, and your teammates. Sport is an extension of life.

15.) Have FUN! Embrace the journey.

References:

1.) Long Term Athletic Development, Canadian Sport for Life, Canadian Sport Centres. 2010.

2.) Dick, F, Sport Training Principals, Lepus Books, 2013.

3.) Hockey Canada Long term Player Development Plan: Hockey for Life, Hockey for Excellence.

4.) Drabik, J., Children and Sports Training, Stadion Publishing, Company, 1996.

5.) Joyce, J., Lewindon, D., High Performance Training for Sports, Human Kinetics, 2014.