Anthony Donskov

Anthony Donskov is the founder of DSC where he serves as the Director of Sport Performance. Donskov holds a Masters Degree in Exercise Science & is the author of Physical Preparation for Ice Hockey.

Seals & Shoulders: It's a Balancing Act

- Font size: Larger Smaller

- Hits: 5299

- Subscribe to this entry

- Bookmark

They say pain can be a humble teacher, a somatic response from the CNS to avoid certain movement/exercise. After bi-lateral shoulder surgery and enough rehab to make Dr. Drew look like an amateur, I can say that pain has been a humble teacher in helping me design exercise protocol for my current athletes and clients. In conjunction with these injuries is the education from the likes of Mike Reinold (The Athlete’s Shoulder, Optimal Shoulder Performance), Robert Donatelli (Physical Therapy for the Shoulder), and Eric Cressey (Optimal Shoulder Performance). These experts have aided me in the process of designing appropriate screening and protocol for my business. As coaches, it is our job to design safe and effective exercise. Below are five ways to enhance the function of the shoulder.

1.) Screen, Screen, Screen:

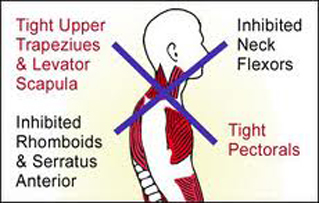

Most people move poorly and not enough. Athletes with previous injuries mask inefficiencies with lack of movement and synergistic dominance. We need to screen both statically and dynamically to access our clients’ movement. One of the “common” impairments we see as coaches is what Janda refers to as “Upper Crossed Syndrome”. We live in a “anterior dominate” society. Tightness in the upper traps, levator scapula, pec minor and major tilts the scapula forward. This narrows the subacromial space which can lead to external impingement (Bursal sided), and shuts down the function of the middle traps (retract the scapula) and lower traps (upward rotation and depression). With this knowledge, we as coaches can design appropriate protocol to counteract these problems.

-

Roll/Stretch/Soft tissue work: Pec minor, major, levator scapula.

-

Activate: Serratus, middle, lower traps. “Poor posture and muscle imbalance often seen in patients with a variety of shoulder pathologies is often the result of poor muscle balance between the upper and lower trapezius, with the upper trapezius being more dominant. (Reinhold, Escamilla, Wilk).”

Upper Crossed Syndrome

2.) Cuff Strengthening:

We need to strengthen the rotator cuff! Simply stated, the function of the cuff is to center the humeral head in the glenoid fossa. Most athletes’ have poor static stability coupled with the fact that only 1/3 of the humeral head sits in the glenoid fossa. Take look at the diagram below, the seal represents the scapula, the ball is the humeral head, and the contact point is the glenoid fossa. Get the picture coaches? Strengthen the cuff!!!

Don’t:

-

Use low reps

-

Heavy weight.

-

This causes synergistic dominance of the deltoid.

-

Overwork the cuff!!!

Do:

-

Promote cuff balance

-

Cuff strength (get on progressive program)

-

Cuff Endurance

-

Promote dynamic stability

Cressey, Reinold (Optimal Shoulder Performance)

Seal/RC Analogy

3.) Thoracic Mobility:

Thoracic mobility provides a stable base of support for the scapula. We need mobility in the thoracic spine to accommodate the rotating scapula, which provides dynamic positioning of the gleniod relative to the humerus. Take a look at the diagram one more time. If the seal cannot move effectively than the ball will fall off of its nose. This can lead to rotator cuff pathology, impingement, and a trip to the doctors’ office.

-

Mobilize the T-Spine

4.) Avoid Certain Movements:

The pathology involved will determine the avoidance of certain exercises. External impingement, internal impingement (overhead athletes) and congenital laxity will all be treated differently as will the tissue tolerance of each athlete/client. Having had both shoulders operated on, I consider myself a human guinea pig when it comes to what not to do with regards to issues involving the shoulder. I train athletes (hockey players) that typically are presented with AC joint and external impingement (Bursal sided) pathologies. I try to address these issues by soft tissue work (please see above regarding upper crossed syndrome), while avoiding certain exercises that will compromise the healing process.

Avoid:

-

Front Squats (AC pathology)

-

Olympic Lifts (AC pathology)

-

Overhead Pressing (this narrows the subacromial space in healthy shoulders).

-

Certain variations of pressing

5.) Push/Pull:

I cannot equate this to an exact science, but through practical application I thoroughly believe that for every push exercise we need a minimum of two pulling variations (horizontal or vertical). Again, we are an “anterior” dominant society sitting most of the day with slouched shoulders and a forward head posture. After we sit all day, the general population feels that the “8 minute Abs workout DVD” with 1000 push ups, 1000 crunches and an extra 20 minutes on the elliptical machine (with a slouched posture) is a good workout. It’s no wonder why clients come in with some sort of shoulder issue. We need to open up the subacromial space and focus on retraction and DOWNWARD (lower traps) pull of the scapula to combat these issues.

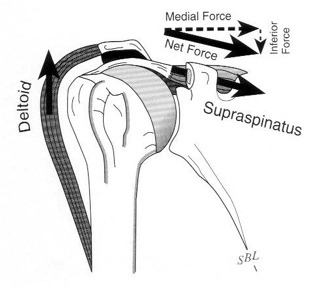

Heaving pressing with lack of pulling/retracting can lead to shoulder injuries. The diagram below illustrates the force couple relationship between the cuff musculature and the deltoid. If the deltoid overpowers the cuff musculature (which can happen with lack of cuff strength and sitting on the bench press all day), the humeral head will migrate superiorly and make contact with the acromion. This leads to impingement. The value of pulling exercise cannot be undervalued when designing appropriate protocol for both athletes and weekend warriors.

Photo Courtesy of: MikeReinold.com

It may seem redundant, but issues such as ACL prevention, speed programs and shoulder “savers” are nothing more than a well-designed strength and conditioning program. These mobility exercises, stretches, and movements can be directly inserted into your current programs to avoid potential shoulder pathologies. We can also use this information to focus our efforts on rehabilitating (with the help of a PT) clients that may currently t have shoulder pain. It doesn’t hurt to learn from the best either (Cressey, Reinold, Donatelli). As coaches we need to constantly educate ourselves in providing the best service for our clients and athletes. After all that is how we make a living!

References:

- Reinold, M, Escamilla, R, Wilk, K, Current Concepts in the Scientific and Clinical Rationale Behind Exercises for the Glenohumeral and Scapulothorcic Musculature: Journal of Orthopedic and Sports Physical Therapy, Vol. 39, No. 2, February 2009.

- Cressey, E, Reinold, M, Optimal Shoulder Performance: From Rehabilitation to High Performance, DVD, Copyright 2010.

- Wilk, K, Reinold, M, Andrews, J, The Athlete’s Shoulder, Churchill Livingstone, 2009.

Anthony Donskov, MS, CSCS, PES, is a former collegiate and professional hockey player, founder of Donskov Strength and Conditioning Inc., (www.donskovsc.com) and Head Instructor/Director of Off-Ice Strength and Conditioning for Donskov Hockey Development (www.donskovhockey.com). He can be reached at info@donskovsc.com .