Anthony Donskov

Anthony Donskov is the founder of DSC where he serves as the Director of Sport Performance. Donskov holds a Masters Degree in Exercise Science & is the author of Physical Preparation for Ice Hockey.

Strength Training for Hockey: 3 Qualities often Overlooked during the Off-Season

- Font size: Larger Smaller

- Hits: 7356

- Subscribe to this entry

- Bookmark

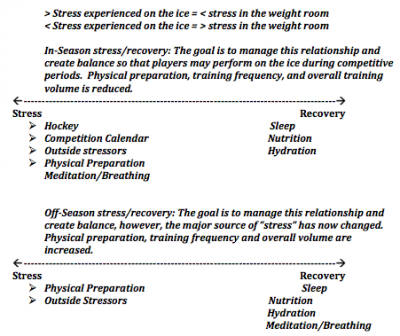

The sport of hockey is extremely demanding. Players reaching speeds of up to 30mph is the equivalent of hundreds of small car crashes occurring throughout the course of a 7-8 month season. Physiological, psychological and mechanical stressors mount during this time. It is during this period that the strength and conditioning practitioner faces a major challenge; the law of competing demands; In other words, how to balance stress so that players performs optimally when it matters most on the ice. This job changes during the off-season when the major stressors of competition are removed. The off-season, although often limited in time, is paramount in terms of physical preparation and the application of additional stressors that may not be appropriate during the period of intense competition.

The law of competing demands during the In-Season and Off-Season for the competitive hockey player.

Below are three qualities often overlooked during off-season/preparation period for hockey players. I believe these qualities are crucial for continued athletic development, efficiency and sustainability.

Position: Posterior Pelvic Tilt/Internal Rotation of the Ribs

Any machine, including the human body, operating in poor position leads to decrease efficiency, increase demand in fuel to accomplish common tasks, and an increase in the possibility of chronic overload. Poor position is the equivalent of riding a bike with a rusty chain. It may take you across the finish line, but efficiency and structural integrity are compromised and in the long run mechanical breakdown is inevitable. Hockey is played in a flexed hip position placing both concentric and isometric stress on the hips and quadriceps during long duration force application. The specificity of this mechanical position places postural adaptation on the player facilitating certain muscle synergists and inhibiting, or turning off others. If the hip flexors are constantly facilitated there is a high probability that the pelvis will be pulled into an anteriorly tipped position. This may cause impingement and mechanical issues within the joint. The practitioner may think of the hip joint as the shoulder joint of the lower body. An anteriorly tipped scapula immediately places the humeral head in a compromised position. Ron Hruska, founder of the Postural Restoration Institute sums it up eloquently: “Is an acetabulum over a femur any different than an acromion process over a humeral head?”

Solution: Create adjacent stiffness of the anterior core musculature and facilitate the hamstrings. This serves to stiffen adjacent structures, and reposition the pelvis posteriorly, thereby taking pressure and pull off of the tight, overactive hip musculature. “It is reasonable to think that if these lengthened muscles are activated, thereby resetting the length tension relationship of the muscle spindles, the muscles on the opposite side of the system would begin to let go.” (1) One of my favorite, simple to use resets is the 90/90 Balloon breathing technique used by PRI. This exercise posteriorly tilts the pelvis engaging the hamstring musculature, while simultaneously internally rotating the ribs allowing for optimal diaphragm function and abdominal support. Think of this position as facilitating muscles that are many times inhibited during the mechanics of the hockey stride and lengthening muscles, which are constantly being concentrically and isometrically overworked.

Used with Permission from the Postural Restoration Institute®, www.posturalrestoration.com (2)

Strength Training: “The Conversion Block”

Hockey players are not Olympic lifters, power lifters or 100-meter sprinters. Although variations of all sporting elements are used in the training process, the coach’s goal should always be to move from general to specific in nature. Hockey players need both strength and power BUT must be able to sustain these qualities during the coarse of competition for success on the ice.

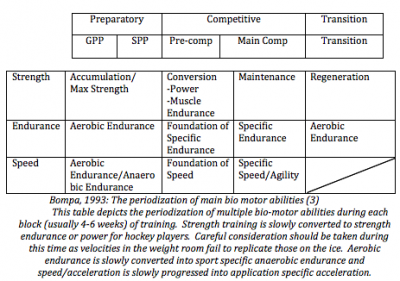

Many Coaches periodize strength by focusing first on accumulation (general strength), then max strength, followed by power. The problem with the “power” conversion phase is that speeds in the weight room fail to replicate those experienced on the ice. The late, great sprint Coach Charlie Francis echoed these thoughts with regards to weight training implications and the power conversion phase for elite sprinters. He states: “I also eliminated the traditional “conversion phase” which sprint coaches had adopted to bring velocities in weight-lifting closer to the sprint speed. I concluded that sprinters extremities moved so much faster in running than in lifting that any increase in lifting speed was irrelevant.” This is true for hockey players as well as velocities on the ice may reach upwards of 30 mph, much greater than those experienced in the weight room while under load.

Solution: These implications have led me to periodize the “conversion” block by focusing on strength endurance, or what Tudor Bompa refers to as muscle endurance. The goal is simple; slowly move from general to specific so that the player is ready for the demands of the season at the correct moment in the training process. This is accomplished by decreasing intensity and rest, increasing volume and challenging the athlete to contract appropriate musculature in the presence of lactate accumulation. The “power” phase has been replaced with the strength endurance phase. This phase leads the player directly into training camp and is most specific to the demands of the game.

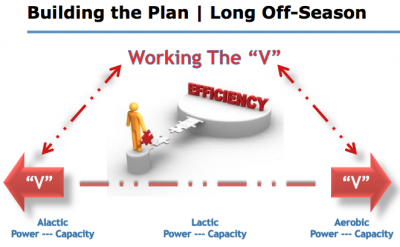

Energy System Development: “Working the V”

“The average player plays between 12 and 20 shifts per game and has an average rest period of 225 seconds between shifts (Wise, 1993). The rest interval between periods is fifteen minutes. It has been estimated that 70% to 80% of the energy for a hockey athlete is derived from the alactic and lactic systems. (4) This does not take away from the importance of aerobic development as these adaptations act as favorable pre-requisites for higher intensity work, while simultaneously giving the players time away from the grind and extended recovery needed when training under lactate anaerobiosis. Chasing the energy system is the same as chasing pain. Many times the problem is the efficiency of the supporting structures and pathways. One of the biggest mistakes I made as a Coach was to constantly tax the lactic system too early and too often. This is a system that adapts and plateaus relatively quickly and causes maximal metabolic disturbance. Coach Frank Dick defines strength endurance, as “training to develop the athletes’ ability to apply force in the climate of lactic anaerobiosis.” He further warns; “Strength endurance training causes considerable wear and tear in the athletes’ organism, and it is possible that a saturation of microcycles with units of this type would cause a loss of mental and physical resilience.” (5)

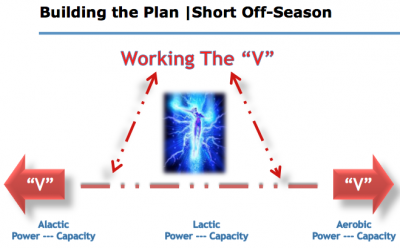

Solution: Working the “V”. Both aerobic and alactic systems are trained first, the former as a supply and recovery system, the later as a system that provides immediate ATP for explosive effort. Both systems are taxed without the buildup of acidosis. The anaerobic lactate system is trained during later blocks of the training plan preparing the player for the demands of training camp. This is known as what strength Coach Mike Robertson refers to as working the “V”. Working the “V” simply means working opposite ends of the continuum, and slowly progressing towards middle ground; the longer the off-season, the more obtuse the angle, and the wider the “V”. Short off-season periods produce the opposite affect, acute angles and a much narrower “V”. As the “V” slowly narrows training shifts to more lactate work building up to training camp and the regular season. This shifts priority towards energy demands that have a strong correlation to sporting demands. The peripheral adaptations of the lactate system are trained approximately 3-6 weeks prior to the commencement of training camp.

There you have it. Three programming qualities often overlooked for competitive hockey players. Positioning, the conversion block and working the “V” are all elements that we at Donskov Strength and Conditioning think are very important when training our unique population of athletes.

References:

(1) Joyce, J., Lewindon, D., High Performance Training for Sports, Human Kinetics, 2014.

(2) www.posturalrestoration.com

(3) Bompa, T., Theory and Methodology of Training, Kendall/Hunt Publishing, 1994.

(4) Bompa, T., Chambers, D., Total Hockey Conditioning, Firefly Books, 2003.

(5) Dick, F, Sport Training Principals, Lepus Books, 2013.